Kyoji Horiguchi was never really given a fair shake of things in the UFC‘s flyweight division. Thrust into a title shot against one of the greatest fighters of all time after only five years of professional competition, coming off a win over Louis Gaudinot, the conditions of his failure were set up from the start.

Horiguchi was forced into the role of the mouse fed to the snake that is Demetrious Johnson as one of the many prospects churned into the flyweight title machine. After losing to Johnson, the perennial top flyweight was relegated to the Fightpass prelims in two of his final three fights with the UFC. At the time of his departure from the UFC, Horiguchi’s career was marked by mistreatment of himself and his entire division. Since that time, Horiguchi has quickly found his home in Rizin Fighting Federation, where the tournament format allows him to truly shine.

For the first time since entering the UFC, the promotional spotlight was on Horiguchi, in a tournament seemingly centered around him. Throughout the Grand-Prix, Horiguchi not only headlined his first card in a major MMA promotion but also his second and third. For his part, Horiguchi made the most of his opportunity, turning in dominant performances over opponents who are far more impressive than their names may appear to those fans who only watch UFC events.

A Different Kind of Karate

Horiguchi comes from a point karate background, holding a second-degree black belt in Shotokan. Consistent with this background, his style is characterized by the distance management and evasiveness of a traditional point-karate stylist, aided by bouncy in-and-out movements. However, one large difference separates Horiguchi stylistically from the wide world of karatekas. Put simply, the boy can box.

Point karate is an odd sort of contest, appearing halfway between a real fight and a game of tag. The first competitor to land a legal blow (or sweep, or throw) scores and all strikes are treated equally. The lunging body blow that grazes the chest and leaves the initiator in no position to follow up scores the same point as a hook that lands square on the jaw.

The oft-mentioned mantra of boxing, hit and don’t get hit, translates into point karate as “touch and don’t get touched.” The object of the game becomes maintaining distance over everything else, as any moment spent in proximity to an opponent’s weapons presents a danger of being touched. Strikes are generally kept to the longest weapons – long straight punches, linear kicks, and shifting blitzes to cover distance quickly. Exchanges are rare and unsophisticated, and head movement is entirely unnecessary.

As a training method, point-sparring is an excellent tool for developing a fighter’s distance management, but a reliance on point-sparring leaves one unprepared in exchanges. This presents a tried-and-true method of victory against karatekas from a point-sparring background. If they can be forced into the pocket, either through pressure to eat away their space, or by letting them lunge in on the lead and counterpunching, they can be beat.

Enter Horiguchi. Horiguchi has dipped into the vast well of boxing in order to patch up the weaknesses in the pocket inherent to the point-karate meta. Using head movement better than any karateka I’ve ever seen, Horiguchi will weave under counters after lunging in with his straight, often catching a left hook as he comes up. Unlike many karate fighters who punch with their heads straight up and on the center line, Horiguchi will slip his head off line on entry, or dip down in exchanges to make opponents miss.

Horiguchi’s footwork contains a mash-up of boxing and karate techniques. Amid the in-and-out bouncing of a karateka, Horiguchi uses small steps to adjust his positioning, as any good boxer would. Horiguchi will periodically draw his lead leg back in his stance and step out with his right leg, in a classic boxing sidestep. Horiguchi also pivots to line Shintaro Ishiwatari up as he tries to circle to the outside. He uses pivots consistently to take angles for attack, exit safely after exchanging, and avoid his opponent’s attacks.

Unlike most karateka, Horiguchi has layered footwork and defense in exchanges. Here he bounces outside Gabriel Oliveira‘s lead leg to land a straight to the body, before stepping back inside. When Oliveira steps out with a lead hook, Horiguchi pivots to square him up, landing a counter straight while dipping under the hook, then comes up with a lead hook of his own while pulling his head away from Oliveira’s return.

Defensive Responsibility

The shifting blitzes so commonly used by karateka are a great way of covering distance against an opponent determined to maintain it at all costs, but they often get the user into trouble in continuous contests when opponents may not want to give ground. These blitzes commit to a linear charge, giving opponents an opportunity to pivot off and break the line of attack. Because of the lack of head movement present in most karatekas, these blitzes also leave them ripe for counters.

Lyoto Machida darts in with a committed straight on Mauricio “Shogun” Rua, letting his rear leg drift forward as if he’s prepared to continue the rush as Shogun gives ground. But Shogun doesn’t back up. Instead, he slips inside the straight and lands a crushing overhand that sends Machida to the canvas.

Horiguchi uses the traditional blitzing combinations from time to time, but he has several tactics to cover up the defensive openings they present:

Horiguchi leaps into range with his lead hook, dropping his level as he throws it to bring his head down and out of the immediate path of his opponent’s strikes. As Oliveira backs up, Horiguchi continues his momentum, shifting forward with the straight right. But instead of barrelling straight into his opponent and exposing himself, as soon as his right foot touches down, Horiguchi dips his head behind his shoulder and springs off the foot, exiting out the side at a safe angle.

When Horiguchi starts his blitz and the opponent refuses to give ground, Horiguchi will slip outside and collapse the distance entirely, preventing them from capitalizing on his committed attack. Horiguchi will either use his attack to secure a tie in the clinch or fall into a shoulder-on-shoulder position and bump them, disrupting their balance and further closing the window on counters. Note in the last sequence against Oliveira, Horiguchi immediately recovers from his attack and shifts out at an angle, before backstepping with a lead hook as Oliveira tries to follow him.

Here Horiguchi launches into Manel Kape with the straight, but Kape manages to slip it, though he takes himself out of a balanced stance while doing so. Horiguchi capitalizes by continuing his forward momentum and bulling into Kape, knocking him off balance to set up an overhand.

Although Horiguchi’s savvy in the pocket prevents opponents from easily finding counters when he launches into an attack, Kape had some success slipping in an under-hook and tying up when Horiguchi committed to his straight. Horiguchi’s elbow comes so far away from his body when he commits to the straight, and carrying his momentum forward makes it easier for opponents to tie up if they can avoid the punch.

Karate Tactics

Though Horiguchi has added boxing into his game to patch of some of the holes left by point karate, his Shotokan influence is still prominent. The bouncing footwork and linear stance of Shotokan allows Horiguchi to rapidly close or create distance. It also works perfectly as a tool for delivering feints and manipulating rhythm.

One can set a certain rhythm in bounces to condition an opponent. Once that rhythm is broken, either by delaying or extending the tempo of bounces, or shortening or lengthening their coverage, the opponent is left reacting on the first rhythm and is unprepared for the break. Horiguchi will bounce backwards at a consistent pace and, once the opponent knows how much distance needs to be covered to reach him, take only a short bounce back and quickly fire off a counter as his opponent commits.

The bouncing footwork is great for setting up entries. Horiguchi feints an entry, prompting Oliveira to back up. Horiguchi then bounces backwards before taking a full bounce forward and then a half-bounce. This half-bounce acts as a stutter step, making his attack arrive faster than Oliveira expects. Oliveira is unprepared as Horiguchi springs into a leg kick, having only just regained his footing.

Another technique ripped straight from Horiguchi’s karate background is his lovely skip-up kicks and knees. Horiguchi will bounce in with both legs, touching his lead foot down first. From there, he’ll either spring directly off his lead foot into a knee or replace the lead foot with his rear foot and throw the lead leg as a kick. This results in a kick that is incredibly fast and hard to see coming, as well as capable of covering large amounts of distance due to the skipping set up.

Horiguchi spends most of his time in a heavily bladed stance, which affords him quick, easy linear movement at the expense of lateral movement. When he wants to quickly cover a large amount of lateral distance, he’ll step into a square stance and begin strafing. It’s important to note that this square stance is almost solely for movement, as there are few offensive or defensive options available, and getting hit in a square stance can be devastating as it lacks the ability of a staggered stance to absorb shock.

After exiting an exchange, Horiguchi steps into a square stance and begins circling off the ropes. As soon as Kape is close enough to threaten him, Horiguchi is back in his strong, staggered stance and ready to respond. When Kape leaps in with his lead hook, Horiguchi slips inside of it and plasters him with a straight that sends him to the canvas.

Horiguchi used this technique in a similar manner to defeat Shintaro Ishiwatari in the finals of the Grand Prix:

Ishiwatari attempts to time Horiguchi bouncing in with a lead hook, but Horiguchi is able to exit in time to make the hook miss. Horiguchi steps back into a square stance and begins circling, drawing Ishiwatari onto him. Ishiwatari follows to cut him off, anticipating his continued circling. As Ishiwatari steps in with a jab, Horiguchi stops abruptly, having stepped back into his staggered stance, and parries the jab while lancing Ishiwatari with a counter right to put him out cold.

On his way through Rizin’s bantamweight Grand-Prix, Kyoji Horiguchi ran through four impressive opponents with ease. The only real trouble he was in at any point came when Manel Kape dropped him with an illegal headbutt near the end of their fight. Not only has he destroyed every man put in front of him, but every fight since his first in Rizin has brought Horiguchi an exciting finish.

Although his run through the Grand-Prix was glorious, it seems Horiguchi has nearly exhausted his options for competition in Rizin already. The top-5 flyweight has a tough decision ahead of him in the near future. He can stay with Rizin – a promotion focused as much on star building as it is on providing competitive fights – and be one of their main attractions, beating impressive, but sub top-5 opponents. Or he can take another crack at the UFC’s flyweight division and with it, a chance at beating the truly elite competition, but also a chance at being under-promoted and relegated to the Fightpass prelims.

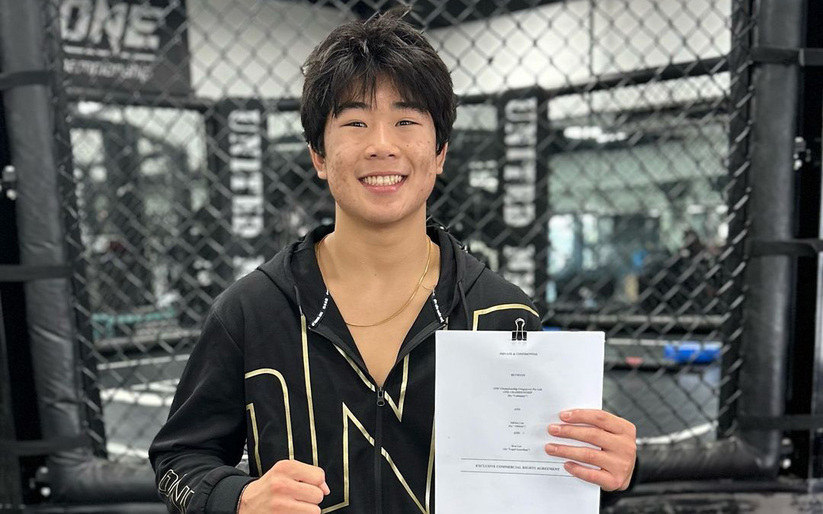

Main Photo:

Embed from Getty Images