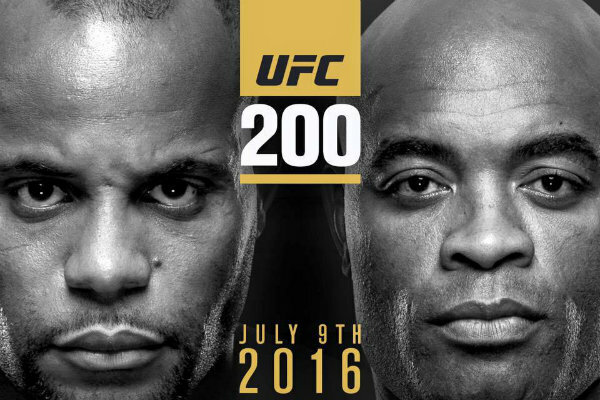

UFC Fight Week Part 3 of 3: Breaking down Daniel Cormier vs. Anderson Silva

UFC 200: Tate vs. Nunes

July 9, 2016 | Las Vegas, NV

PPV Main Card: 10PM/7PM ET

FS1 Prelims: 8PM/5PM ET|PT

UFC Fight Pass Early Prelims: 6:30PM/3:30PM ET|PT

Light Heavyweight Bout (3 Rounds)

(C) Daniel “DC” Cormier [17-1] vs. #5 (MW) Anderson “The Spider” Silva [33-7]

The Show Must Go On

As of this writing, the main event for UFC 200 has changed a record four times since the card first began forming underneath its original headliner, a rematch between Conor McGregor and Nate Diaz. A tug-of-war regarding McGregor’s promotional duties resulted in the match being scratched and eventually rescheduled for UFC 202. After brief speculation, a new main event was announced.

UFC light heavyweight champion Daniel Cormier versus UFC interim light heavyweight champion Jon Jones for the unified light heavyweight title was certainly a bout deserving its status atop the most stacked card in UFC history. But that bout, too, fell by the wayside just days from the event after Jones—a man who achieved the seemingly impossible by allowing his antics outside of the cage to overshadow his prodigious artfulness within it—was flagged by the United States Anti-Doping Association for testing positive for banned substances. Jones and Cormier were both pulled from the card and the three-round contest between Brock Lesnar and Mark Hunt was elevated to main event status.

Then word came down from UFC president Dana White that Cormier would still be competing on the card. But against whom?

Speculation was abundant and fervent. Would it be former Strikeforce champion Gegard Mousasi, who was also at UFC 200 and would therefore be ready, on-weight and cleared to compete? Would it be former Pride FC champion Dan Henderson, with whom Cormier had previously tussled, who was coming off of an impressive knockout of Hector Lombard? Or could it be current UFC middleweight champion Michael Bisping, who threw his hat into the ring on Twitter upon hearing of Jones’ violation?

As it turned out, none of them were ultimately chosen. Instead, it was former middleweight champion and pound-for-pound great Anderson “The Spider” Silva who was selected to face Cormier in a three-round, non-title bout at the newly-minted UFC 200: Tate vs. Nunes, as the title bout between women’s bantamweight champion Miesha Tate and Amanda Nunes was the only full-fledged title contest remaining on the card.

At 41 years old, Silva has begun to show his age. Winless since 2012, the man who’d drawn comparisons to Muhammad Ali doesn’t impress upon his opponents—or audiences, for that matter—the aura of invincibility he once did. There still have been flashes of brilliance in every one of his past four performances and one would be foolish to dismiss Silva, who thus far remains unbeaten at 205 pounds in the UFC, however few are counting on him to capture another title.

Strengths

Almost guaranteed to be the smaller man every time he enters the cage, Daniel “DC” Cormier’s offensive arsenal is predicated on pursuit and initiative. The former Olympian is constantly pressuring his opponents towards the cage while maintaining a solid base from which to attack. He operates at a considerable length disadvantage, meaning the champion often seems to skip into range in order to plant his feet and throw strikes. This also means that most opponents can, with merely a lateral or backwards step, leave him whiffing at air with uppercuts and hooks and stutter stepping forward to reengage.

This is where his most potent weapon comes into play: the single-collar tie. Lacing his left hand behind his taller opponent’s neck, he uses his low center of gravity to pull their head forward while he, the shorter man, can still stand upright. If initiated in the center of the cage, he can steer the action to its edges, where he does his best work. It could be argued that Daniel Cormier is the best clinch tactician against the cage not named Jon Jones currently competing in mixed material arts. At close range, Cormier employs bruising uppercuts to the head and tenderizing knees to the body and thighs in order to deplete his opponent’s stamina and combative resolve. Once able to break away from this entanglement, those facing the champion often eat a few shots on the way out and in short time find themselves back in precisely the same position, as he seldom affords them even the briefest respite.

Cormier’s grappling acumen is so fine-tuned it could easily be mistaken as effortless. While he can certainly take down anyone inside the cage from almost any position, he still does his best wrestling work where he strikes most effectively. Against the cage, Cormier often transitions to single leg or double leg takedowns at the end of striking sequences that force opponents to turn all their focus towards guarding their head and torso, thereby opening up access to their hips. The beauty of this arrangement is that if he fails to get the takedown or occasional throw, he can, as the more diminutive man, stand upright again and continue striking where he left off.

Anderson Silva’s approach to combat is based largely on evasion, misdirection and opportunism. Though the version of “The Spider” we’ll be seeing this Saturday will be a slower, less durable version than the one who reigned atop the middleweight division for almost seven years, he remains one of the most dangerous fighters to ever compete inside the cage.

From a defensive perspective—his go-to mode—Silva is all about movement, slips, counterstrikes and feigns. Foregoing the traditional defensive method of keeping one’s hands up and ready to deflect incoming strikes, he instead relies on his exceptional head movement, lateral footwork and misdirection to make opponents overextend, miss or become entranced by his rhythm and open themselves up to strikes. A southpaw, he baits his foes with a variety of kicks, a pawing jab and a plethora of taunts and then pounces like a spring-loaded javelin. If his opponent is the first to attack, he dodges and briefly circles off in preparation to return fire or, if circumstances appear ideal, lock on his dreaded Muay Thai clinch in order to go to work with knees.

When Silva takes the initiative, he is a deft cage cutter, mirroring his opponent’s movements until they are precisely in position for any number of his seemingly boundless array of strikes. Despite a few setbacks against outstanding competition, Silva is still one of the finest feigners in the UFC and can bait even the most disciplined fighters into overcommitting. While he does not possess one-punch knockout power, his precision and timing more than compensate and provide him with openings to land fight-altering blows.

Silva has good anticipatory takedown defense at range and his legendary clinch dissuades all but the most headstrong and confident grapplers from engaging him in closed quarters. However, his sub-par ability to return to his feet after being placed on his back has forced him to develop a reliable guard from which he can threaten with submissions and, if opportunity arises, slip out from beneath his foe and stand back up.

Weaknesses

Despite moving down from light heavyweight, Daniel Cormier is not an exceptionally powerful puncher. He’s also not a particularly deft cage cutter against actively mobile opponents. Against Alexander Gustafsson, Cormier was forced to give chase around the cage for much of the contest and was caught multiple times with intercepting strikes while closing in. He experienced similar difficulties against Jones, whose length deflected nearly all strikes but those thrown in the closest of quarters. Further, the light heavyweight champion is especially susceptible to strikes to the body at distance.

To get into close range, Cormier basically just steps into his opponent and tries to avoid strikes while doing so. If he manages to tie up or land a few strikes, terrific, but when his opponent is able to slip, step away and reengage with strikes of their own, these brief skirmishes place him in poor position, vulnerable to strikes and takedowns.

Once the gold standard of MMA striking, Anderson Silva has now competed long enough to see the bloom wear off of that distinction. His wide, karate-style stance, at one time the picture of potential dynamism, appears glaringly faulty due to its susceptibility to kicks and opponents’ lateral movement. In his fight with Nick Diaz, we saw Silva try to keep his hands high in expectation of the flurries Diaz would no doubt throw his way. That trait carried over into his next bout against Michael Bisping. However, both of those men were still able to land on the Brazilian, who seemed to drop his guard at the end almost every combination. Old habits indeed die hard.

While talented at stuffing takedowns shot from distance, Silva has never excelled at staving them off forever and eventually winds up on the ground against most opponents intent on taking him there. He is far from exceptional at gaining and maintaining wrist control once an opponent is inside his guard, meaning he gets hit often while on his back.

Contrasts

Daniel Cormier, a great pressure fighter despite his trouble cage cutting, is still at a reach disadvantage in this bout despite fighting a man who spent most of his career competing 20 pounds lighter. That Silva will likely also hold the edge in speed means that Cormier must be even more aggressive than usual. “The Spider” does his best work when starting off slowly, feeling out his opponent’s tendencies and developing a rhythm. Cormier must not allow him to do this.

Silva, the first southpaw “DC” has faced in more than three years and the first since he dropped to light heavyweight, is considerably more mobile than Frank Mir was when the AKA product faced him back in April 2013. His deficiencies in cage cutting against a fighter as mobile as Silva may also cause him difficulty, as there are few competitors who can punish opponents for making mistakes as well as “The Spider.” Patience, however, is not a strong suit for Silva, who can sometimes be baited into wild exchanges. He also deals with frustration rather poorly; facing an opponent who insists on tentatively moving in on him, he’ll often throw his hands up, concede position with his back against the cage and invite his aggressor to come and get him—a godawful strategy against a fighter like Cormier.

There of course are other variables to consider. Cormier was training for a similar opponent in terms of striking output, but it would be silly to suggest that Silva and Jones are interchangeable in regard to their skill sets. But even though Cormier’s camp did not prepare him for a southpaw Muay Thai specialist whose penchant for in-cage creativity seemingly knows no limits, at least he had a camp. Silva, on the other hand, basically walked in off the street. The 205 pounds they’re fighting at? Cormier had to rigorously cut down to reach that weight. Silva might have to skip a meal or two. And while the Brazilian will be the taller man come fight night, he’ll by no means be larger than Cormier, a powerful fireplug of a man who can launch 250 pound men into the air and slam them back to the mat with ease.

If Silva is to win, he must finish the fight early. Cormier trained for a five-round war with the consensus greatest fighter on the planet and, barring any remaining issues with his ACL, will be the best version of himself we’ve seen so far. Silva must stay mobile when upright, force Cormier to miss, make him pay dearly for doing so and utilize the front snap kicks that he was largely responsible for popularizing to keep the champion from advancing on a straight line. When the clinch is engaged, he must fight to separate by using knees and elbows inside and avoid Cormier’s obligatory strikes while circling off. He absolutely must not concede the takedown.

For Cormier to get his hand raised, he must dismiss the urge to match Silva with strikes while in the clinch and dive immediately for his opponent’s legs once he gets within close quarters. The heavier, stronger man, he needs only to secure three takedowns, total—one per round—to win a decision or place him in optimal position to end the fight.