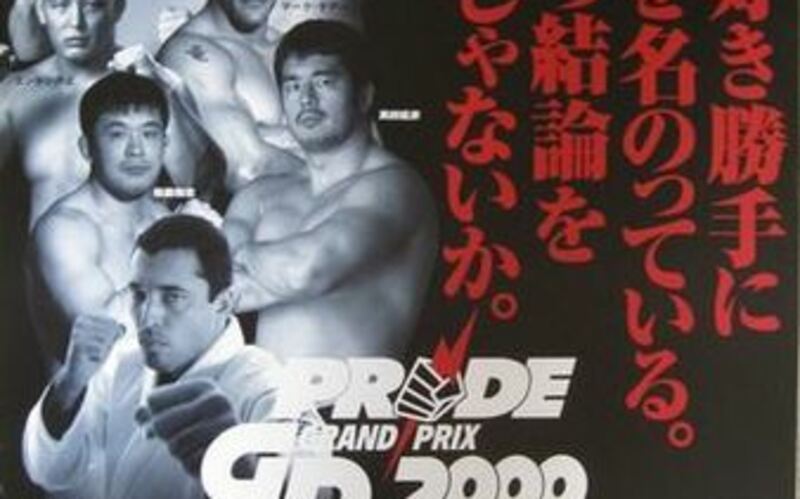

2000 PRIDE GRAND PRIX

It has been nearly twenty years since the 2000 PRIDE Grand Prix. Almost every single widespread innovation in MMA – with the exception of the increased focus on weight cuts – has made the sport safer for the athletes. Testing for performance-enhancing drugs has never been stricter. You cannot kick someone in the head while they are on the ground, or elbow them at the base of the spine. Indeed, many are glad to see the end of the Wild West days of MMA.

Yet, for MMA fans that just makes the period of 1997-2007 – when PRIDE not only never died, but lived – especially important. So many elements of the sport had yet to exist, and there was so much that had yet to be stripped away. It kept some of the spirit of the truly mad days of slaps and wrestling boots on one side of the Pacific and no-holds-barred brawls on the other. Yet by this point, the sport had built up enough momentum that promoters were able to get genuine talent to participate. In one hand wads of cash; in the other, perhaps a gun to force a reluctant manager to comply.

It is against this web of yakuza influence, legal PEDs and chaotic matchmaking that the single oddest tournament in MMA history took place. Yes, even more odd than UFC 3. Every single thing that could have gone wrong, did. Yet; it is something rare and unique and could not have possibly taken place in the modern-day. More than that, the very chaos of the proceedings allowed for some of the most memorable moments in MMA history. Triumph, tragedy and farce all at once.

There were no weight divisions for this tournament. Grounded knees were legal. The rounds were 15 minutes long. It was not simply a battle against an opponent. It was a battle against the limits of what martial artists are capable of.

2000 PRIDE Grand Prix – The Lineup

The 2000 PRIDE Grand Prix was simply far too studded with interesting careers to go through them all here. Nobuhiko Takada, a legendary shoot-style pro-wrestler press-ganged into fighting some of the best in the world despite limited real skills. Alexander Otsuka, a man with a far stronger strength of schedule than anyone with a 5-13 record should ever have had. Enson Inoue, the closest thing the 21st century saw to a samurai. All are worthy of their own articles.

Here, we will simply be following a single thread through the tournament, as each player loses to another until we reach the end.

The Sandman: Home-cooking

It is tempting to start our story with its most obvious protagonist, Kazushi Sakuraba. Certainly, he will get his turn. But if we are to tell this story sequentially, we must actually start out with Guy Mezger (no “t”). A wrestler and karateka training for MMA under the auspices of Ken Shamrock at the Lion’s Den, Mezger would emerge as competent in every area in a sport still filled with specialists.

So it was that he engaged Sakuraba in a match reminiscent of every anti-wrester versus striker match since. Mezger exploited his jab at range, thudded right hands home, and threw kicks after stuffing takedowns. Sakuraba’s low kicks were checked, his improvised spinning attacks dodged. Even when Sakuraba started managing to get Mezger to the floor, Mezger would slowly get back to his feet. Over the course of the 15 minute round – something else we will never likely see again – Sakuraba’s offence was fully nullified.

Mr. Sandman

But while Sakuraba is better known as the perennial underdog, both in size and the odd tournament rules he would later be working under, the unpleasant reality of combat sports is that to unscrupulous officials all over the globe no man can really be an underdog in their hometown. This would reflect itself most commonly in Sakuraba’s career by late stoppages – which only really favoured him in the cold calculus of increasing his chances for victory and resulted in many extended beatings.

However, in this instance, Sakuraba was gifted a draw and therefore an extra round. Extra rounds are often viewed dimly by fight fans. This is largely because of how enthusiastically they were employed during certain K-1 matches as mulligans for otherwise beaten hometown fighters.

While it is possible to wonder if Mezger would have prevailed had he continued, his coach Ken Shamrock intervened. Shamrock was furious at both the judging and that Mezger would be forced to fight an unagreed second round. He pulled out, and the official result was a TKO victory (corner stoppage) for Sakuraba.

So it was that Sakuraba’s tournament run would continue, a shady beginning soon to be overshadowed by his most famous battle. But it would only be the first of the tournament’s oddities to come. For while the first round would take place in January, the second, third and final rounds would all take place in May, just under twenty years ago.

The Gracie Hunter: Gracie = Crazy

So then, to Sakuraba. In a tournament built for David-versus-Goliath matchups, Sakuraba was the David to all and the Goliath to none. Having specifically put on weight in order to appear more impressive for the purposes of pro-wrestling, Sakuraba was loathe to lose it. The result was a man who would have fought at welterweight nowadays regularly battling at 205 lbs (PRIDE’s middleweight division) and sometimes, like now, even against heavyweights.

But against Royce Gracie, three-time UFC tournament winner, Sakuraba was not particularly undersized. But he was fighting uphill in another regard. Sakuraba had broken the decade-spanning Gracie winning streak after defeating Royler Gracie. The Gracies disputed the victory, since the fight was stopped by the referee. Therefore, for the rematch, they demanded unlimited rounds (15 minutes each). This fight would only end by submission or knockout.

Gracies were no stranger to unique rules. Rickson Gracie would demand special rules banning knees and elbows to the head before his bout with Masukatsu Funaki. But this time these special rules were designed with the sole purpose of making sure that whichever of them won, there could be no excuses. Truly, none can claim the Gracies were not in this instance putting their money where their mouth is. The demands did however massively increase the tension between Sakuraba and Royce, with Sakuraba even wearing diapers to a press conference to mock the potentially unlimited rounds.

There are many epic duels in MMA. There are also many historically important fights. Despite its fame, Sakuraba/Royce Gracie I was neither (though at least more respectable than their second encounter). Since both combatants were grappling specialists it proved almost nothing about the wider MMA meta, and later on Sakuraba would battle Renzo Gracie, the most successful of the Gracie family in MMA in a far more exciting and dramatic encounter.

Kind of a let-down

The only thing that truly made this fight stand out from the others is its length. At 90 minutes, one can watch six non-main event fights during its run, and indeed that is recommended. Even Sakuraba’s famous theatrics could do little to make the stall fest more exciting. The knowledge that the match could go on and never stop forced both fighters to adopt an extremely low work rate, and aside from a few moments where both nearly caught the other in submissions, it was either both men clinching in a corner or Sakuraba slamming low kicks into the legs of Gracie as he laid in guard. So it was, then, in the end, his legs battered by an hour and a half of relentless pounding and victory slipping away, Royce finally gave in.

Brazilian fighter Royce Gracie (right) battles Kazushi Sakuraba from Japan during fight action at the Los Angeles Coliseum, Saturday, June 2, 2007 before an estimated paid attendance of 54,000.Gracie won the fight with an unanimous decision after three rounds. (Photo by Bob Riha Jr/WireImage)

The expectations placed on Royce always loomed larger than the man himself. He did not have the mythical legend of Rickson, he was not well rounded like Renzo. Handpicked to represent the Gracies at the first few UFCs, Royce was stuck with the reputation as the runt of the litter; picked solely because his less impressive physique would make his martial art seem more impressive. Perhaps that’s why Royce would try so hard to recapture the old glories by fighting Ken Shamrock and Sakuraba in Bellator.

Ultimately, it mattered for nothing, and Royce’s opportunity to rise above his brothers once and for all ended after the towel was thrown in. Sakuraba had taken Royce’s own rules and turned them against him.

But here is where fate truly entered the picture and would decide the tournament. Even as Sakuraba tried to recover from his ordeal he would be thrust back into the fray once again far sooner than he anticipated.

Iron Head: The Wheel of Fate

Kazuyuki Fujita was himself yet another pro-wrestler turned successful shootfighter. Rather than the incredible grappling nous of Sakuraba, however, Fujita relied upon a natural advantage. Pound-for-pound, we have probably never seen a greater chin in mixed martial arts. Fujita was simply impossible to truly knock out and more than one opponent would unload a flurry of shots upon him only to wear themselves out with Fujita unaffected. Ken Shamrock would even give himself heart palpitations after several minutes of battering “Iron Head” and was forced to throw in the towel for fear of a heart attack.

It is, therefore, the greatest irony that one of the most durable mixed martial artists of all time would be so badly injured that he would be forced to resign from the tournament. After his fight with Mark Kerr – he of the legendary Smashing Machine documentary – Fujita was so injured that just as his fight with Mark Coleman began he threw in the towel.

Certainly, he cannot be blamed for simply taking the show money, but the result was that since an official bout took place Coleman would not fight any replacement and would go on to the third round totally fresh. Igor Vovchanchyn would be forced to fight again almost immediately. And Sakuraba would have almost no time to recover from his 6 round marathon with Royce.

The result was that Sakuraba would be thrown in against Vovchanchyn far quicker than he had anticipated.

Ice Cold: The End of the Road

While he has been called the proto-Fedor, Igor Vovchanchyn’s career actually ran in reverse. Rather than starting as a grappler who eventually learned striking, Vovchanchyn was a kickboxer who took to grappling after being handed two early submission defeats. He would then go on a terrifying run, tearing through smaller promotions before arriving in PRIDE. A 37 fight unbeaten streak, the vast majority of which were KOs or TKOs.

Having just disposed of Gary Goodridge in ten minutes, Vovchanchyn would be almost immediately set to fight against Sakuraba.

This then, was truly the moment that defined Sakuraba. It would have been so easy to give in; he had just fought Gracie for an hour and a half. “Ice Cold” weighed 22 pounds heavier. The first combination from Vovchanchyn sent Sakuraba cascading backwards from the centre of the cage all the way into the ropes. An impossible task, the end of the road for the Gracie Hunter. How much more could be asked of him?

Then Sakuraba circled back in and flicked a jab into Vovchanchyn’s face, followed by a missed straight. A few minutes later, he completed another one of his famous low singles and dragged the Ukrainian to the mat.

What a guy

When Vovchanchyn took mount, Sakuraba would let him have his back and looked for Kimuras. Frustrated, Vovchanchyn literally hurled Sakuraba into the ropes and struck him. Vovchanchyn would ragdoll Sakuraba with suplexes, Sakuraba would bring him down with low singles. Finally, the Ukrainian started bringing the ground and pound to bear and Sakuraba was covering up. Sakuraba rose again but Vovchanchyn cracked him with a punch that sent him tumbling back down. Sakuraba laid in guard, shot from guard for a low single, then fell back.

But Sakuraba had simply hit the limits of human endurance. He tried one last upkick, then fell back into guard. His body could give no more. A few moments later, the round ended. Just as Mezger had done, this time it would be Sakuraba who would be calling it a day before the next round could even start.

The biggest irony of all, however, was that like a curse, Sakuraba’s disadvantages would be passed onto Vovchanchyn. Since Mark Coleman did not have a single opponent in the third round since Fujita forfeited, he had spent the entire time recuperating. Vovchanchyn would, therefore, be going into the finals against an opponent who had fought one less fight. Vovchanchyn, on the other hand, had fought two opponents in a row. He would have to take every moment of the Ken Shamrock/Alexander Otsuka superfight to rest before the finals.

The Hammer: PRIDE 2000 Grand Prix Final Round

Mark Coleman was probably past his best. He had come to PRIDE on a three-fight losing streak, extended by a “loss” to Takada, which was almost certainly a faked fight. He was still an impressive opponent, a mountain of muscle with a passion for wrestling. Coleman was certainly no one to fight if you were not at your best.

He’ll make you an offer you can’t refuse

The final match was almost anti-climactic. Coleman took Vovchanchyn to the ground almost immediately. The “Godfather of Ground-and-Pound” then proceeded to unleash a fifteen-minute onslaught of strikes and submission attempts. Vovchanchyn managed to survive till the second round, whereupon he was taken down immediately again. This time, Coleman was able to get into north-south position. From there he employed something else you would never see nowadays; the dreaded grounded knees to the head. Within a minute, “Ice Cold” was tapping to strikes.

The 2000 PRIDE Grand Prix had finally come to an end.

2000 PRIDE Grand Prix, Grand Folie, Grand Gloire

What a mess. Coleman beat Vovchanchyn with the latter at a significant disadvantage; Vovchanchyn fought a close fight with Sakuraba after Sakuraba had an hour and a half fight with Gracie; and Sakuraba himself should have lost to Mezger if the judging was fair!

A truly bizarre tournament. Nearly everything that could go wrong, did. Real-life is not Street Fighter. We were left with far more questions than answers from these fights…

And yet; amid all the shadiness and the special treatment and the sheer bad luck of it all, 16 of the most fascinating people in the history of MMA participated in the 2000 PRIDE Grand Prix together. Through the adversity of their opponents and their situations, some of the greatest moments in MMA history were made. And those 16 people gave us something truly special; something that we never saw before.

Something we have never seen the like of, not in the twenty years since.